Understanding Cross-Market SERP Cannibalization

September 28, 2022Hreflang Deployments Simplified

October 18, 2022Why Google Needs to Support hreflang

There is an interesting set of threads on Twitter and some comments on Reddit about the value of hreflang and due to the recent depreciation of the International Targeting report, does Google still need to support hreflang. There were also comments that “Google Should be able to use some of its recent technology to sort it out and make things easier for internationalization.”

I have wanted to write this post for a while to try to simplify why hreflang, despite being a challenge to implement, is more beneficial to website owners than it is to Google. In 2002 when I was running Search at IBM, I and a couple of other multinational SEOs lobbied Google to implement various methods for us to indicate the market for our same language websites/pages. We needed a solution because Google was primarily showing IBM’s US website in other English-language markets. Every solution we recommended would require considerable resources by Google to “sort it out” with little to no direct benefit to them. Remember, Google is not a public utility but a company trying to make money and must allocate its resources accordingly. Finally, in 2011 they launched hreflang, which made it relatively easy to designate the market purpose for each webpage.

Full Disclosure, I have spent the last 25 years working with some of the largest brands in the world to make them rock globally and the implementation of hreflang helped solve one of the biggest cross-border challenges we encountered. To leverage this solution, my team and I developed Hreflang Builder, to make it easier for companies to implement hreflang and fix their cross-market cannibalization problem. For the past seven years, we have seen how well it works and roughly estimates saving companies nearly a billion dollars in lost revenue due to traffic cannibalization and cart abandonment And you can bet those companies also have a vested interest.

Let me try to frame my argument for Google’s continued support of hreflang by reiterating the simple purpose of hreflang and using its syntax to illustrate why you can benefit from it, and Google should continue to support it.

First, to be crystal clear, Google does not have a problem understanding the language of a website. It can relatively easily determine whether a website is in English, Spanish, or Arabic and even many exotic languages. If you use Chrome browser go to websites that have remote tribal language versions and you will see the translate button appear showing that remote language and your browser language preference.

Second, Google’s goal is to present the most relevant result to the searcher. It is the company marketing teams that want Google to show a specific market version of that page. When there are multiple same-language versions of a page without specific elements to indicate a market what is Google to do?

Purpose of hreflang

The purpose of hreflang is for the site owner to “explicitly indicate their language or region-specific pages.” This has been reinforced in the entry paragraph to Google’s updated Tips for Localized Websites guide stated below:

If you have multiple versions of a page for different languages or regions, tell Google about these different variations. Doing so will help Google Search point users to the most appropriate version of your page by language or region. Even without taking action, Google might still find alternate language versions of your page, but it is usually best for you to explicitly indicate your language or region-specific pages.

Let’s unpack these two statements from Google it should be pretty clear how Google uses it and the explicit benefit to the site owner.

- A specific URL and its language or language region – the benefit is removing the ambiguity of the language target of the page and eliminating the need for Google to “try” to figure it out.

- The alternate versions and their language or language region – same as above, the list of alternates both removes the ambiguity of the target market and directly points Google to them. By listing the alternates, Google can index the pages and clearly understand they are present to target a specific language market removing the potential problem of being a duplicate or canonical variation of another previously indexed page.

- The language or region designation helps Google understand which version of your page to show in specific language markets.

If I oversimplify this syntax for a hreflang cluster, it is a list of URLs and their respective language targets. What should be relatively simple to implement is nearly impossible for some websites due to the challenges I outline below.

All of these points are value propositions for the site owner. Does Google lose by showing your US webpage in Canada or the UK? No, it does not. We could argue that it benefits Google to find the additional 100 language variations of your page so they can index them. I would disagree, as most of them will be near or exact duplicates adding unnecessary clutter to their index and increased overhead to figure out what market they are for.

I believe both entities benefit from this exchange. Presenting the better market version of a webpage to searchers make Google’s results better, increasing user satisfaction of getting them directly to the appropriate page, and the site owner benefits from not having to redirect them or high cart abandonment due to incorrect market matches.

Can Google Figure “it” out without hreflang?

A number of those experts commenting suggest “with all of Google’s technological ability, it should be able to figure “it” out. The “It” is which language/market version of a page to show in each market SERPS. In my opinion, while Google might be able to “figure it out” for some sites, most multinationals don’t make it easy and will benefit from being able to designate the specific country. Let’s break down what Google needs to detect and understand to present a market-specific page in a local version of the search result.

What Country does the Website/Page Represent?

Google will try to present results to searchers that are not only relevant to their query but also make them relevant to their location. Google typically will present “local results” based on the query language, the searcher’s IP location, and the browser language preference of the searcher. In this simple scenario, how would Google determine a website is for Australia?

There are a number of well-written documents on this process, with the most relevant from Google in their Guide for Managing International Websites listing the methods they use to determine local-specific URLs. Roger Montti, in a SEJ article, captures some of Google’s John Mueller’s tips for targeting a specific country from a Webmaster Office hours session. For those who want a deep dive into how Google determines the language in the query check out this in-depth SEJ article from Eli Schwarz.

Let’s recap some of the information from these brilliant guides and my 30 years of experience working with global brands.

ccTLD

The ccTLD (country language top-level domain) of .com.au indicates that it is registered in and for Australia. That is the best method to indicate the website’s intent. For all practical purposes, a website with a ccTLD should represent that market. Despite this being the best signal and the top recommendation for deploying a global website, many multinationals do not use it. In our 2019 research of hreflang deployment, only 10% of the 165 brands we evaluated were using ccTLDs consistently.

While a ccTLD may designate a market, it DOES NOT restrict that website to only that market. In this screen capture in Bolivia for Pampers. There is not a ccTLD for Bolivia, and per the country selector, it would be the Latin American regional site. But in this case, that is second to the Argentina website.

Language

While there are some markets like Japan, Latvia, Thailand or Myanmar where they have a language that is unique to their country Google could assume a website in Burmese or Latvian language is for those markets. This would be impossible with multi-country languages and is exactly why the problems increase with languages spoken across multiple markets like English, Spanish, and Arabic.

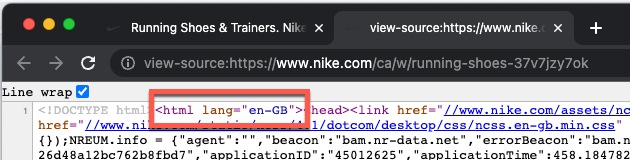

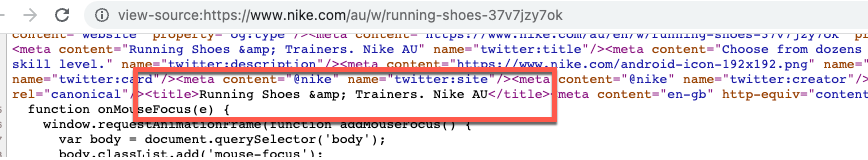

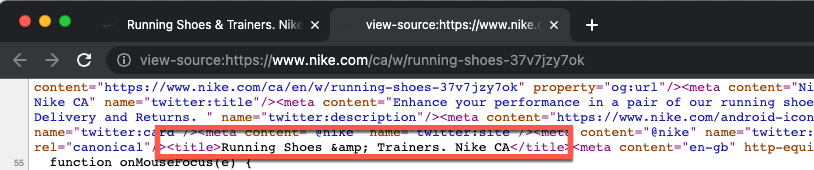

Web developers will often suggest using the HTML Lang tag. I did a research project about 10 years ago and found nearly 87% of the tags were not accurate and often took on the site it was cloned from or where the CMS code was downloaded. The screen capture below shows two examples from Nike.

Both the running shoe category pages for Nike Australia (above) and Canada English (below) both use en-GB as the language. You can argue that it is British English, so it is correct, but this is the exact problem with using this tag. For Google to set them using this tag they would need to be “en-AU” and “en-CA” respectively. I found 5 of Nike’s markets using en-GB as their language code. The US website was using “en” and as we know American English is its own version.

Currency

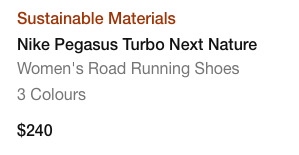

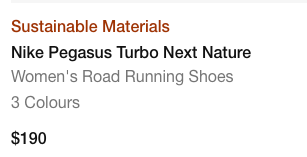

Another potential signal could be currency. The problem is many websites don’t use the full name or even the three-letter abbreviation for the language and only use the currency symbol. The symbol could work for the Indian Rupee or Nigerian Naira as they have unique currency symbols. This is exactly why Product Schema requires the three-letter code for the currency abbreviation to remove ambiguity with symbols. Maybe when the majority of websites get Schema in place we can revisit that signal. Back to our friends at Nike, both the Canadian English and Australian websites use the universal dollar symbol for currency.

Market Designations on the Page

Another signal could be actually listing the country designations somewhere on the page. Again using Nike as an example, the only reference to Canada or Australia on the entire page was the abbreviation of the country at the end of the title tag. There was not any address, phone number, or any other element on the page that indicated this page had anything to do with Australia or Canada. Do you think the Canada site could be mistaken for one in California?

There was not any address, phone number, or any other element on the page that indicated this page had anything to do with Australia or Canada. Do you think the Canada site could be mistaken for one in California?

Making It Hard For Google to Figure it Out

As you can see from the previous section, the task is already pretty challenging for Google to figure out the market using logical signals. Now let us look at the real world and the typical chaos that is the infrastructure of multinational websites, especially fast-growing eCommerce websites it becomes nearly impossible. The following are some scenarios where Google may not be able to “figure it out” as easily as we want them to require the need for assistance. To recap, Google needs to understand the country and language for a website to present it correctly to a searcher in a market.

Challenge #1 – Mixed Domain Formats

Whenever I have to defend Google’s inability to detect a company’s geolocation strategy, I present this scenario which typically matches their situation. Let us suppose a website uses a combination of ccTLD along with dot-com domains, subdomains, folders, and in some cases, all of these simultaneously. Yes, they may all have the same product page. Yes, the ccTLD versions they should understand, but what about non-standard domains and folders – how would Google even know they are all the same company? Maybe if all registered in the same Google Search Console account, they would need to factor that into logic, and why would they do that? In my experience, a company with this level of decentralization is unlikely to have an organized, all-inclusive GSC setup.

With Hreflang Builder, we have identified over 400 different formats of ways companies designate their country and language combinations. For one website, we have a regex of over 1,000 characters just to parse the multitude (53 variations) of mixed domain cc/ll variations.

Most often the DevOps person will point to the country locator page as their roadmap to their geolocation system. While NOT a signal used by Google to determine the country of a website, one suggestion by a commenter was to use the company’s country locator. This could be an interesting option, but unfortunately, most country selectors are incorrect. We often start our hreflang setup by using what is listed on the locator, but the majority of the time, the websites listed are incorrect. Let’s use BMW as an example. On their country selector page, most of the markets appear to be using ccTLDs. They list Australia as https://www.bmw.com/en-au/home.html, but this redirects to https://www.bmw.com/en-au/home.html. So despite having the ccTLD and referencing it on the country locator, they redirect to a folder structure. There was little consistency, with some redirecting the ccTLD to a folder structure and others not. Another challenge of using the country selector is the problem of regional websites. On Pamper’s Country/language page is well laid out but many of the links to markets, especially in Latin America point to the same website.

Challenge 2 – gTLD with folders or subdomain

This challenge is similar to the above challenge they use a dot-com or other global top-level domain with subdomains for folders to designate the individual market versions of the website. Let’s start with the simple problem – If a website uses /de or de.mysite.com does the de represent language or country? For example, Dove soap, what does https://www.dove.com/uk/home.html represent? Is it the United Kingdom or the Ukrainian language? Sure, if Google goes to the page and sees English, it may assume GB. What about the /de page – is that Germany or just the German language? You may suggest Google can follow a pattern of the folders being language or country. In the case of Dove, they cannot follow a pattern since Dove uses that folder interchangeably for language and country.

It gets further complicated with regional sites where one or more of the markets in the region have a local site. For example, Huawei’s consumer products group has a https://consumer.huawei.com/latin/ website but also has Spanish-language websites with folders for most of the markets in Latin America. What should Google do with this Latin website? Huawei does not use a country locator, but their hreflang has set it to Guatemala. Without hreflang, is there any way Google could know their intentions, or would this site be ignored, shown in multiple markets, or cannibalized by the /latin site? Do we expect Google to create a country language matrix and remember all of the nuances of your website? If there were only a way to do that – oh yea, there is using hreflang.

Challenge 3 – Different Brand Names

A little less common but this challenge is all too common for CPG/FMCG companies where either the ccTLD is taken or they use a different brand name for the product across markets. Similar to scenario 1, an English language website for a similar product with a different brand name, how will Google sort it out? For example Axe body spray is called Lynx in Australia. If the searcher uses the brand name it is easy to sort out but what if they are looking for “body spray” then without any location signal Google could show either website. Is it Google’s job to know they are the same product with regional trade names?

Similar to different brand names are domains with different formats. For various reasons, domain names may vary or be hyphenated or abbreviated; how would Google know they are the same brand family and specific to a market?

Challenge 4 – Google’s MUM Technology

Let’s add a challenge that is created from Google’s technology that could impact market site performance by benefiting searchers. Google’s overview of the MUM presents this exact scenario. The scenario in their overview is a searcher researching climbing MT Fuji and does a specific query related to the views of the mountain. The best result is in Japanese and that is presented to them. How could that be a challenge to a website owner? Let’s say you are a Japanese company that offers tours to Japan targeting western markets, and you have a website for the US and UK and Japan. On all three websites, you have a page about the amazing views of and from Mt Fuji. The team in Japan has added additional information, images and richer content to the Japanese page with views from different angles, locations, or times of the day. Based on users’ prior searches, Google MUM algorithm could show them your Japanese page with a link to translate that page. The problem will be the traffic that should have gone to the US will not count for Japan but any traffic to a brand site is beneficial. What if that great content on the Japan site pushes the user to book a hike to the mountain? Again a booking is god but what if translated booking link takes them to the Japanese language booking page. They will be lost and potentially abandon the website and choose another vendor in English.

Should Google Have to Figure it Out?

Just these few scenarios above help illustrate the massive task it is for Google to try and understand the country of a website also makes hreflang nearly impossible to implement and audit, but this is not the fault of hreflang so I ask. Should this be Google’s job? Why can’t they just show the best match page in the SERPS and call it a day? What is in it for Google? The user wants information on a Ford Mustang, and despite being in Ireland, they get a US webpage. Some DevOps will argue that is fine since they will just do an IP detection when the listing is clicked and send them to Ireland – problem solved, no hreflang necessary. While this solves for the click, it does not solve for non-local market click abandonment or the other risks and challenges IP detection creates for search engines.

Are you Willing to Rely on Google to Figure it Out?

We all agree that hreflang can be difficult to implement but those complications are really not the problem of hreflang. Just these few scenarios above help illustrate the massive task it is for Google to try and understand the country of a website. Some have stated on Twitter since Google sunset the International targeting tool that, they now must be able to understand the country or why they would get rid of of the targeting tool.

There are some in the search industry that are calling for Google to eliminate hreflang because it is complex to understand, hard to implement, hard to validate, and even more challenging to show value in using it. Yes, it is hard, I am on the front lines and know it is a challenge to implement, but it is not the fault of the system itself. This is one of the main reasons I have been advocating for companies to move it out of the SEO team and move it into either the Growth Team or Web Infrastructure, where they can understand the negative impact of their infrastructure and hopefully improve the foundation of the market websites.

If we take time, as I suggested in the intro paragraph, to understand and, most importantly, accept the simple purpose of the hreflang element, that is nothing more than a way for a site owner to designate a language/language region for the page. That simple designation gives Google a clear indication of its purpose that enables Google to show the page in the correct market; no matter how much dysfunction your global web infrastructure throws at it, my friends, that is a win for the site owner. That is also why that if Google technology evolves where it can detect the correct market there is nothing wrong with giving it a little help by using hreflang.

Most of all, remember Google’s goal is to present the most relevant result to the user despite what you want to present. Is it Google’s job to understand your family of websites and present them as you wish? If you believe it is, meet them halfway and do your part by telling them through hreflang tags. If you have any form of cannibalization Hreflang Builder can help you recapture that lost opportunity. To get started, you can book a consult or demo with the Hreflang Builder Team or signup to start your hreflang project.